Gila Wilderness

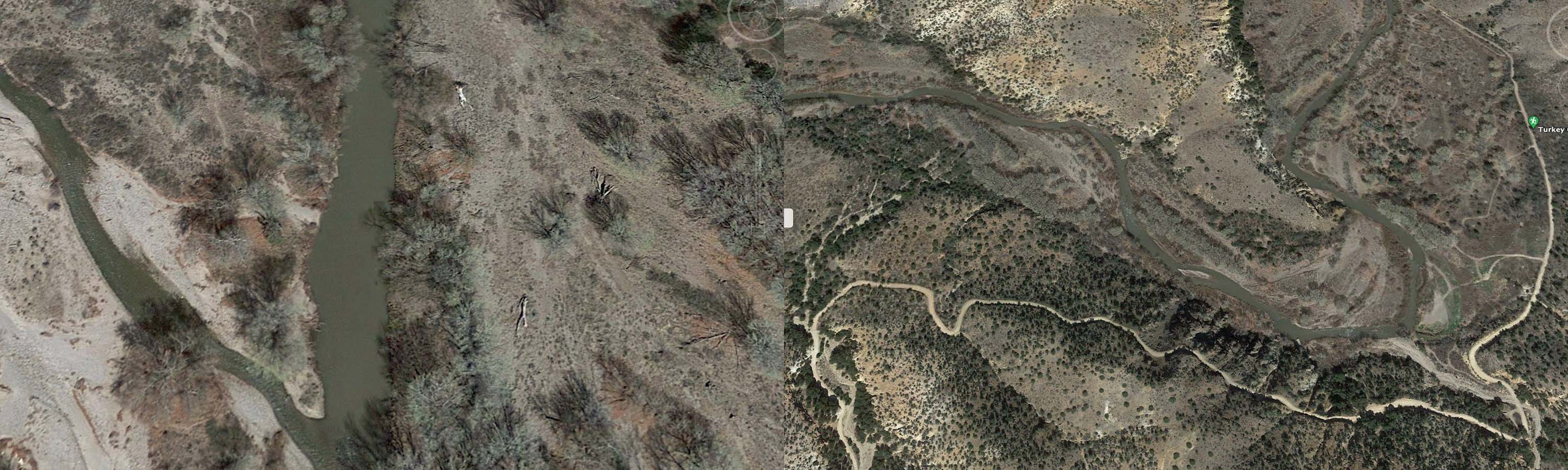

The headwaters of the Gila River begin on the western slope of the continental divide. The West fork of the Gila flows southeast near the Gila Cliff Dwellings, once inhabited by the Mogollon culture between (600-1400 AD). The confluence of the Gila river forms slightly south of the Gila Cliff Dwellings where the West, Middle, and East Fork join into the Gila Wilderness which is only accesible by unpaved road that ends near Brock Canyon Ravine. Wilderness camp locations along the river are available to the few who know of their existence. The pristine environment is untouched by the economic influences that drive the land-use south of Gila, and is fiercely protected by environmental and community interests.